Domesticating the prophetic king

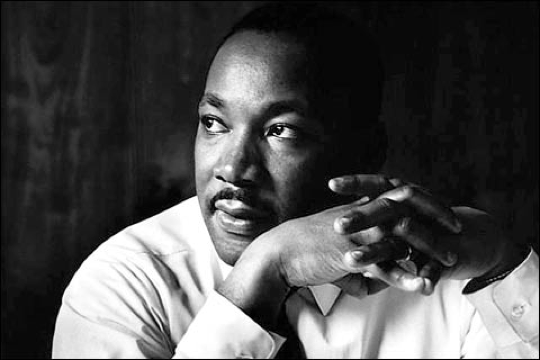

Last month we remembered the legacy of our nation’s greatest public prophet, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King was the moral and spiritual leader of the civil rights movement, the movement that the Catholic monk and writer, Thomas Merton, once described as the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States. Furthermore, Dr. King has had a considerable impact upon me and what I want my ministry to be all about (in fact, a long clip from his “drum major” sermon was played at my ordination).

Last month we remembered the legacy of our nation’s greatest public prophet, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. King was the moral and spiritual leader of the civil rights movement, the movement that the Catholic monk and writer, Thomas Merton, once described as the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States. Furthermore, Dr. King has had a considerable impact upon me and what I want my ministry to be all about (in fact, a long clip from his “drum major” sermon was played at my ordination).

I thought it would be fitting, then, to cut the ribbon of this journal with King.

Even though I feel the national holiday is in some ways a disservice to his legacy (we’ll get to that in a second), I began celebrating it a few years ago with readings and reflections. I spend some time reading or listening to his writings and sermons and also try to work through a biography on him, then I spend some time reflecting on what his life and message has to say to me today.

This year I celebrated with two books and two films. As for the books, one I’ve owned for a while but hadn’t yet read, The Beloved Community by Charles Marsh, and the other I just recently got my hands on, Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, written by the scholar and activist Vincent Harding who worked alongside King. As for the films, I watched one of his first in-depth televised interviews from 1957 and the documentary by Tom Brokaw titled King.

Here are a couple of my reflections this time around.

From protest to reconciliation

Study history and you’ll discover that socially progressive movements and their leaders are almost always oriented toward either protest or reconciliation. Malcolm X exemplifies the first; Desmond Tutu the second. This is what Charles Marsh writes:

“Most often protest and reconciliation appear as dialectical twins who reunite as rivals rather than friends, different goals that sometimes intersect and cross-pollinate but usually diverge and clamor for attention.”

The bus boycott in Montgomery, however, proved that these two trajectories are not mutually exclusive. King’s vision brought protest and reconciliation together, marrying them under one movement. For example, after the victory in Montgomery, King cautioned against any aggressive celebrating or smugness that could possibly appear as arrogant or taunting. His message was clear: “We must now move from protest to reconciliation.”

And one more example. As the movement shifted its attention toward desegregating Birmingham’s downtown merchants and thousands of new volunteers were traveling to Alabama to join the protest, King put together a Commitment Card for every volunteer to sign. The card included ten commandments, the second was a pledge to “Remember always that the non-violent movement seeks justice and reconciliation – not victory.” King understood that the work of protest and reconciliation must go hand-in-hand if the Christian ethic of love is to be realized and lived out.

Sanding off his sharp edges

Exactly one year before he was murdered, King delivered a speech titled “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break the Silences” at Riverside Church in New York. He spoke out against what he called the “giant triplets” of racism, militarism, and poverty. This address was a prophetic showdown with the Powers that be; it was one of the most courageous public speeches in US history; and it certainly contributed to a decline in his popularity.

So while I appreciate the national holiday in honor of MLK (established in 1983 after a long political struggle), I’m saddened by how it’s been used to domesticate the prophetic King. Schools and streets are named after him and politicians’ prayer breakfasts are held in honor of him, yet what is forgotten are the strong criticisms he landed against our nation’s unchecked greed, inequality, militarism, and addiction to violence. We’ve sanded off his sharp and prophetic edges, glossed them over with one simple memory (“I have a dream”), and then tip our hat to this much more palatable King. We’ve tamed our nation’s greatest public prophet while we sit here 40 years later still at war, still believing the myth of redemptive violence, and still preferring free trade rather than fair trade. So how much of his dream has really been realized? We don’t need a palatable King, we need a prophetic King.

And on this note I must add a question. I’m wondering why almost no one knows a Memphis jury that presided over a civil suit brought by the King family in 1999 only needed one and a half hours to make an official ruling that our own government had conspired to assassinate Dr. King? I’m not much of a conspiracy theorist, but I’ve read the trial transcripts which can be found at The King Center. Seventy witnesses under oath testified that a wide-ranging conspiracy existed involving city, state, and federal government agents. William Pepper records the story of this verdict and the twenty-five years of investigation leading up to it. Again I ask, with all the homage paid to King by our politicians and public leaders every year, why haven’t more of us heard about this?

King used to own a gun

King didn’t just pop out of his mother’s womb espousing pithy sayings about peace and nonviolence. In fact, he only became convinced of the power and purity of nonviolence in his late twenties. When he began pastoring Dexter Avenue Baptist Church he owned a gun and kept it in his house; King was no pacifist when he arrived in Montgomery. But by the end of the bus boycott year he had gotten rid of the gun, convinced that it stood in the way of him following Jesus. Later he said, “I was much more afraid in Montgomery when I had a gun in my house.”

This is what encourages me. There was a time when King wasn’t committed to nonviolence and enemy love – but he changed. His convictions grew over time, they developed and hardened, and eventually they crystallized into rock-solid commitments that enabled him to withstand violence and respond with love.

This gives me great hope that people really can change. It reminds me that transformation is possible, that more people can still come to understand that violence only begets violence (as the greatest prophet said, “those who live by the sword, die by the sword”). This makes me hopeful that people will wake up and realize that there are better ways of living. And I’m not just talking about violence and militarism, but materialism and selfishness and spiritual apathy and environmental disregard – and the list goes on.

Here is the NBC interview that King gave in 1957, not long after the end of the bus boycott and at a time when the country was still trying to decide what to do with this black Baptist preacher from the south. I mention it here because King shares his own intellectual journey towards nonviolence – and though I’ll let you watch it for yourself, a couple of lines are too good for me not to mention. (It’s even more stunning knowing that King was only 28 years old when he gave the interview.)

When asked if he was a “gradualist,” meaning was he in favor of the gradual integration of whites and blacks, King responds:

I think gradualism is so often an excuse for “escapism” and “do-nothing-ism” which ends up in “stand-still-ism.”

And when asked about his method of nonviolence, King answers:

Nonviolent resistance has two sides. The nonviolence resister not only avoids external physical violence, but he avoids internal violence of spirit. He not only refuses to shoot his opponent, but he refuses to hate him.

Well, there’s my inaugural post. Thanks for cutting the ribbon with me, Dr. King.