Father, Forgive Us (part 2)

This is my second post on the art exhibit I worked on illustrating the Stations of the Cross after the Holocaust which was on display this past week at the Center for Jewish Studies at Baylor University (the first post can be read here). And it’s fitting that I’m writing this last reflection on Good Friday since we see the vulnerability of God more on this day than any other. The theologian Jürgen Moltmann writes, “At the center of the Christian faith stands an unsuccessful, tormented Christ, dying in forsakenness.”

This is my second post on the art exhibit I worked on illustrating the Stations of the Cross after the Holocaust which was on display this past week at the Center for Jewish Studies at Baylor University (the first post can be read here). And it’s fitting that I’m writing this last reflection on Good Friday since we see the vulnerability of God more on this day than any other. The theologian Jürgen Moltmann writes, “At the center of the Christian faith stands an unsuccessful, tormented Christ, dying in forsakenness.”

This is one of the great paradoxes in the New Testament. Ultimately Christ is victorious, but the victory is won in the strangest of ways. The cross has been described as “victory hidden beneath its opposite” (Luther). All we see on Good Friday is a man stripped naked and executed on a cross.

And for that reason, many of us don’t know what to do with this day. We’re not comfortable sitting with its darkness and death, so we skip Good Friday and go straight to Easter Sunday and the resurrection. Preachers start announcing a week before Easter, “He is risen!” but Jesus hasn’t even been crucified yet!

Good Friday is crucial, for it tells us that God is no stranger to suffering. The cross is God’s choice to enter into human pain – but when we fail to grasp the significance of this, the cross can easily become entirely and only about saving souls.

Calvary is about salvation, but also much more. The cross is the place where systematic evil and injustice are confronted and challenged. Paul says that on the cross Jesus “disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame” (Colossians 2:15).

The cross is also the place where God takes on the full impact of human-inflicted misery and experiences it for himself. God doesn’t approve of suffering – he wants to rid the world of it. And that is precisely why Christ suffered on Calvary. His suffering was not a passive acceptance of evil; it was a protest against evil.

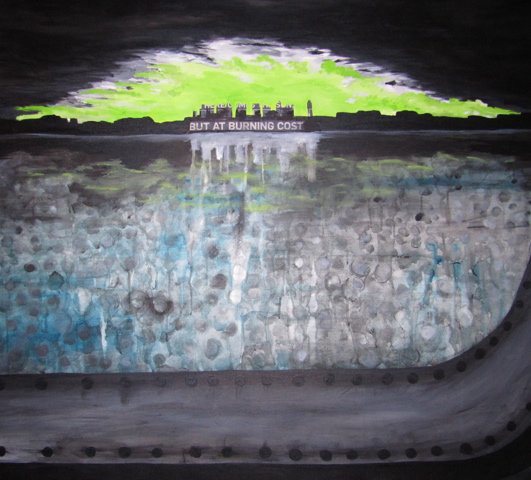

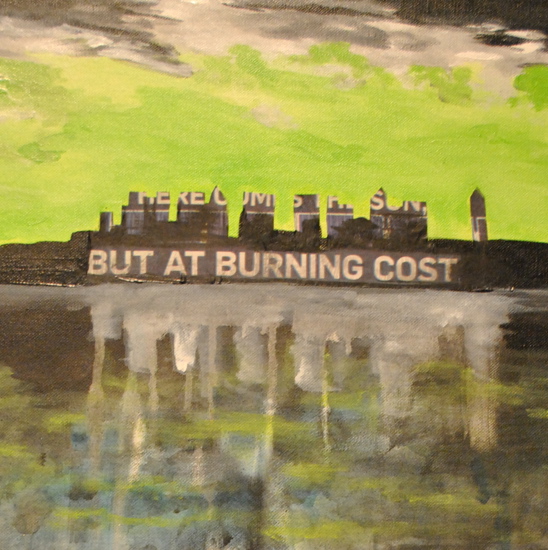

[Station 8, “Jesus speaks to the women of Jerusalem / Known as the “Voyage of the Damned,” more than 900 German Jewish refugees aboard the ocean liner St. Louis are sent back to Europe after Cuba and the United States refuse to accept them.” Artist: Nathalie White]

The Crucified One

But ever since the 4th century (i.e., Constantine and the marriage between Christianity and the imperial state), the church has had a tendency to interpret the passion and resurrection of Jesus in solely triumphalistic terms. Now, don’t get me wrong. Resurrection is central to our faith. The hope of the world begins with the empty tomb. But this joy and hope cannot be divorced from the pain and sorrow of the cross. The risen Lord is also the crucified Lord. After seeing the pierced hands and side of Jesus, Thomas exclaims, “My Lord and God!” (John 20:28). This confession is not merely that Christ has resurrected, but that the crucified Christ has resurrected.

Similarly, Saint Paul declares to the church in Corinth that he has resolved to know “nothing except Christ” – then qualifies his statement with “and him crucified,” lest his readers fail to grasp that the risen One is forever the crucified One (1 Corinthians 2:2).

Nowhere else in history is the character of God so clearly communicated as in Christ hanging from the cross. The cross tells us that God is the God of the oppressed and the forsaken; it tells us that God stands with those who have their backs against the wall.

The message of the cross is that we’re not alone when we suffer – there’s someone else screaming alongside us.

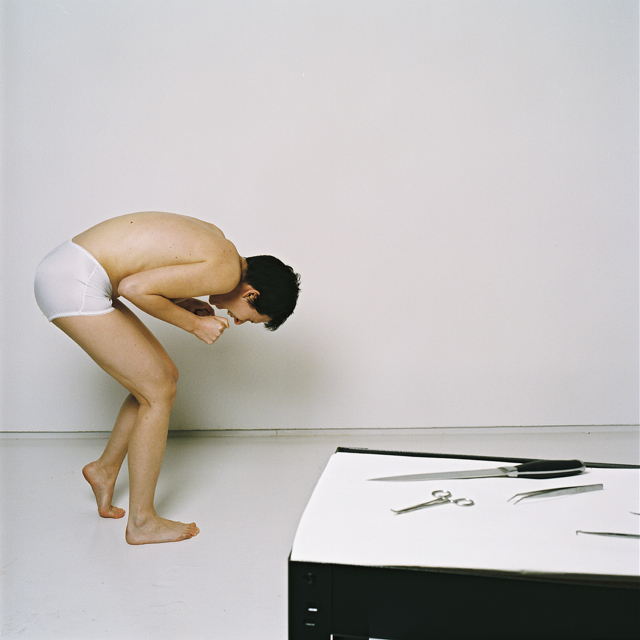

[Station 10, “Jesus is stripped of His garments / Jews are forced to undergo medical experiments and tortures at concentration camps carried out by trained Nazi doctors.” Artist: Misty Keasler]

If Christianity is to have any credibility in a post-Holocaust world, then the authentically Christian idea of the suffering of God in Christ must be rediscovered.

The Darkest Mystery

Our Stations project does not deal with suffering in general, however, but with the supreme atrocity of the Holocaust. Thus, we must go one step further and engage the Stations in light of the concentration camps and crematories.

But how can we? How can the above statements about God’s character be made after Auschwitz and Treblinka? How can the murder of one Jew and six million Jews even be spoken of in the same breath? How is it possible to portray the senseless Holocaust murders while simultaneously portraying the atoning death of Jesus – and especially since most of these murders were carried out by baptized Christians?

We would do well to heed the fierce warning of Orthodox rabbi Irving Greenberg: “No statement, theological or otherwise, should be made that would not be credible in the presence of the burning children.”

I doubt there will ever be a Holocaust theology, Jewish or Christian, that’s able to answer these questions and make sense of this moral dilemma. There is simply no pristine theodicy (defense for God). Nevertheless, the only way forward requires that we move – albeit in fear and trembling – toward an even deeper understanding of what the cross shows us about God.

If God suffered even unto death in the cross of Christ, then this means God not only identifies, but is also present, with all those who suffer and die. The darkest mystery of the cross is that somehow it subsumes the suffering and death of the world into God’s being. As Cyril of Jerusalem wrote around the year 386 AD, “On the cross, God stretched out his hands to embrace the ends of the earth.”

The cross teaches us that God does not abandon the Nazi death camps, but enters into and experiences its pain through the gruesome cross. In Moltmann’s words, “God is in Auschwitz and Auschwitz is in the crucified God.” This is why our art for the Stations of the Cross focuses neither solely on the sufferings of the crucifixion nor on the sufferings of the Holocaust. Both are expressed, for both are absorbed into God’s being.

[Station 14, “Jesus is laid in the tomb / By the end of the war, Europe has lost two-thirds of its Jewish population.” Artist: Francisco Donoso]

The Church’s Vocation and Location

Understanding the cross this way means there is one more message conveyed by our Stations exhibit. This has to do with the future of Christianity and where the church will choose to be in respect to the sufferings of the world

Back in early December I was really struggling with working on this project. I had reached a point of impasse in trying to respond to the horrors of the Holocaust. But then I had a breakthrough while reading Romans 8. I had read this chapter countless times before but had never realized what it meant for the church’s vocation and location in the world.

Romans 8:18-28 tells us, with graphic imagery, that all of creation is suffering in pain. And where should the church be as the world groans? Sitting comfortably and smugly on the sidelines because we’ve got it all together? No, says Paul, we ourselves are right there groaning inwardly as we wait for our renewal and liberation. The church is to be present in the world at the point of its greatest pain; this is to be the location of the church.

And where is God throughout this process? Somewhere far off, sitting in heaven, twiddling his thumbs as he watches the world suffer? No, says Paul, God is groaning, too. God is present within the church at the place of the world’s pain. This is not a detached and indifferent God; this is the God of Jesus Christ, the God who experiences the pain of the world.

The danger of triumphalistic Christianity is that it will always sweep aside the suffering of the world as inconsequential. It allows the church to sit on the sidelines while others suffer since being a Christian is all about “winning” and “victory.” But what if Christianity is actually about sharing in the sufferings of Christ and, thus, identifying with those who are weak and marginalized?

Here’s what this has to do with our Stations of the Cross project. According to Romans 8, the church is not insulated from the pain of Auschwitz – nor Tiananmen Square, Afghanistan, Zimbabwe, or the West Bank – but is called to go to these places of great pain in order that God’s crucified love might be brought to bear on that point.

[Station 5, “The cross is laid on Simon of Cyrene / Gypsies, homosexuals, and Jehovah Witnesses suffer alongside the Jews since they’re also classified as “non-desirables” by the Nazis.”

Artist: Brian Gibb]

N.T. Wright describes this strange and dark theme, which is our birthright and vocation as followers of Jesus, in the following way:

“The present task of the Church is not only to share the sufferings of Christ, but in doing so to share and bear the sufferings of the world – and, indeed, to discover that those vocations are two ways of saying the same thing; so that the pain of the world, which was heaped once and for all on to the Messiah on the cross, is now strangely to be shared by those who suffer with him.”

The church is a part of God’s response to the massive suffering in the world. But in order to alleviate suffering in the world, we ourselves will suffer. The maxim for Jews after the Holocaust has become “Never again.” Christians also need a new dictum, however: “Never again will we stand by and do nothing while people suffer and are oppressed.”

Living in a society obsessed with winning and success, we urgently need to relearn what Good Friday and Christ’s passion mean for the church’s vocation and location in the world. This is perhaps the only way we’ll be able to overcome Christian triumphalism.

Many thanks to the six other artists that helped create this exhibit. I hope these Stations of the Cross, and other works like it, move us to the margins. Maybe next year someone could design the Stations with Juárez or the Gaza Strip in mind.

I hope the Stations propel us to go to the places of greatest pain in the world, for it is there that we shall find our crucified and risen Lord.

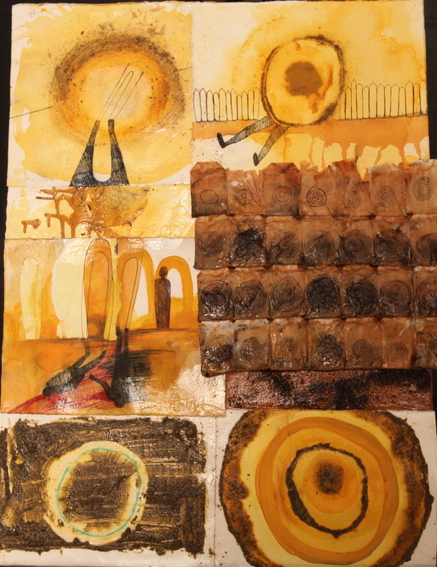

[Station 2, “Jesus is made to carry the cross / Nazis institute a national boycott of Jewish businesses and begin enacting laws to push Jews out of German society. Artists: Nela Emmanuel and Will]