“In the beginning God created, I mean liberated…”

In Romans 8 Paul writes that all of creation groans to be liberated, and I contend that if you listen closely you can hear our world today groaning to be set free from many bondages.

Ever since I gave a teaching earlier this month at Jacob’s Well Church (it can be listened to here) I’ve been thinking about how fiercely concerned God is with one of humanity’s deepest longings – freedom. I’ve decided to write a three-piece post on liberation and what it means to follow a God who always sides with the oppressed. Many thanks to Kansas City local photographer, Danielle Larson, for collaborating with me on this entry by providing the artwork.

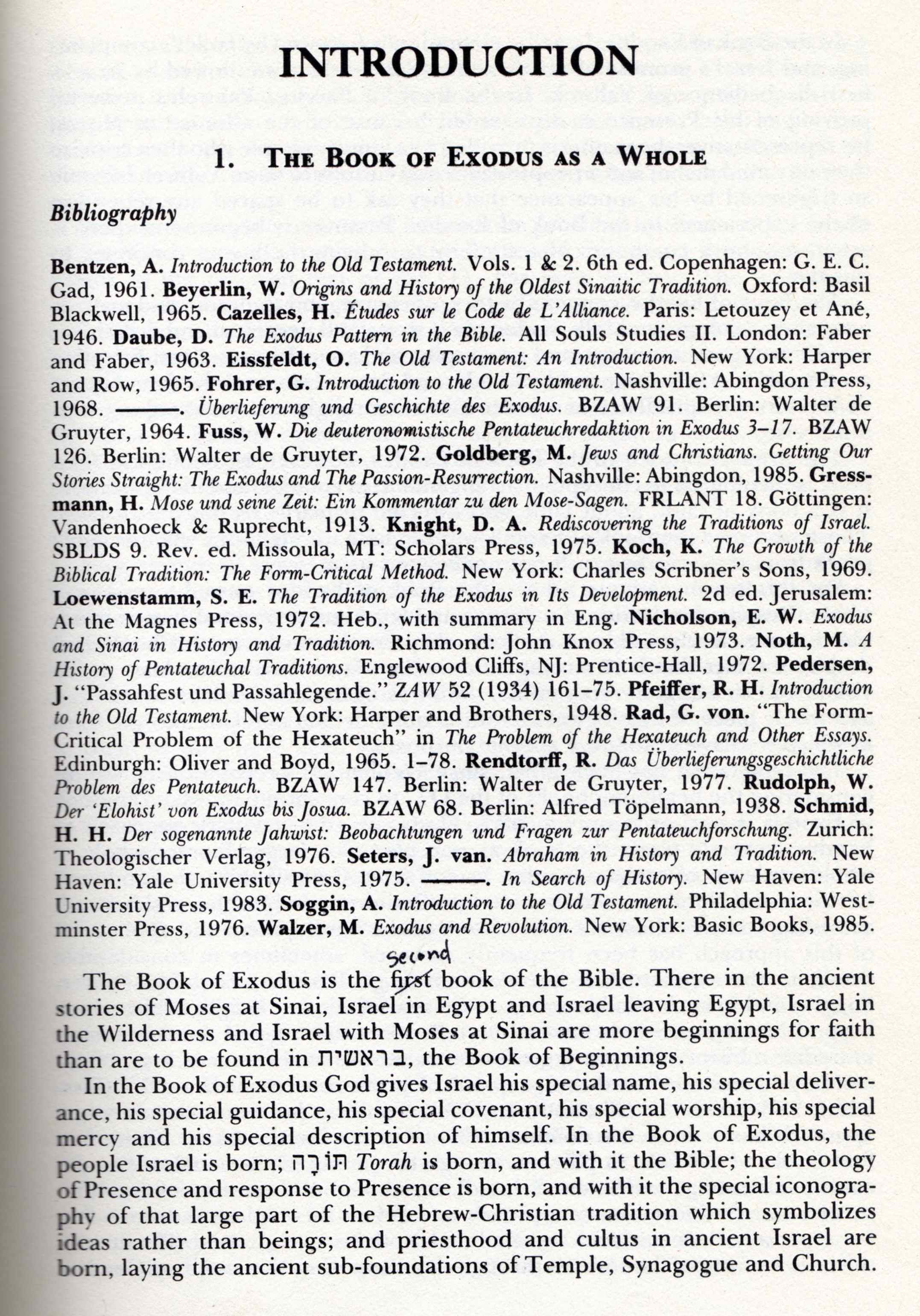

Today’s entry is about slavery, tattoos, God’s divine name, and why Exodus is the first book of the Bible. Let’s start with the last of these since that one might sound a bit ridiculous to you. At least it did to one seminary student.

Since I’m in KC for the summer, every so often I go to the Nazarene seminary in town to study in its library. One afternoon I pulled John Durham’s giant commentary on the book of Exodus off the shelf. Durham is an Oxford-trained Hebrew scholar, and he begins his 500 page (and pound) commentary with these words: “The Book of Exodus is the first book of the Bible.” In the margin I found this correction inked in by a bold and self-assured seminary student.

So this raises the question, who’s right? Is Exodus the first or second book of scripture? Well, it depends on whom you’re asking. Most Christians will say it’s the second book because that’s how it’s arranged chronologically. But if you ask a Jew, they’ll almost certainly tell you it’s the first book.

This is what the French sociologist and theologian Jacque Ellul has to say: “What is not generally known is that Genesis is not really the first book of the Bible. The Jews regard Exodus as the basic book. They primarily see in God not the universal Creator but their Liberator.”

Exodus is central for the Jewish people because they think of God as liberator before they think of him as anything else. Just to prove that I’m not making this up, let me show you how this plays out in scripture. I’ve compiled all the references in the Old Testament that speak of God as “the Creator”: Deuteronomy 32:6; Ecclesiastes 11:5, 12:1; Isaiah 27:11, 40:28, 43:15. There’s six in all.

Now here are all the references to “the God who brought you out of Egypt”: Exodus 3:12, 6:7, 20:2, 29:46, 32:1, 32:4, 32:8, 32:11, 32:23; Leviticus 11:45, 19:36, 22:33, 25:38, 25:55, 26:13, 26:45; Numbers 15:41; Deuteronomy 5:6, 8:14, 13:5, 13:10, 20:1; Joshua 24:17; Judges 2:12, 6:8; 1 Kings 9:9, 12:28; 2 Kings 17:7; 2 Chronicles 7:22; Nehemiah 9:18; Psalm 81:10; Daniel 9:15.

There’s thirty-two of them, and my hands are tired from typing. I think the Bible is pretty adamant that God is to be known first and foremost as liberator. Yet we shouldn’t be surprised – at the beginning of the first book (yes, I’m talking about Exodus) this is exactly what God promises he’ll be known for throughout history.

A peaceful sound to some, a piercing noise to others

The first three chapters paint a very dark picture of life in ancient Egypt. Of course, it wouldn’t be so dark if the story was told from the perspective of those in power with wealth and privilege. But it’s not. It’s told from the perspective of poor people living under the oppressive rule of an empire.

A famine and food shortage had originally forced these people to migrate to Egypt. They were living in a foreign land, but at least they were free. Eventually, however, the rulers of this land saw there was a profit to be made off these people, so they forced them to do hard manual labor under horrible conditions and paid them almost nothing for it. The great Egyptian empire was built on the backs of poor immigrants. (I’ll let you make the connections.)

But then, in the third chapter of Exodus, the storyline suddenly shifts direction. Everything changes when the word natsal is thundered forth from the heavens. God comes to a man named Moses and says, “I have seen the misery of my people, I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to natsal them.” (Exodus 3:7-8)

The Hebrew word natsal means “liberate,” “rescue,” or “deliver.” When pronounced by God, this word has a polarizing effect on those who hear it. To those on the underside of power, natsal is the sound of redemption. It is good news – no, great news. It means their suffering has not gone unseen and their plight is not forgotten. But to those who use their power to oppress and exploit others, natsal has a terrifying ring to it. It’s a piercing noise, for it means someone has blown the whistle on them and exposed their crooked schemes. Natsal signals the end of oppression and the beginning of freedom.

The logic of God’s liberation

God says he’s going to rescue these slaves out of Egypt and liberate them from a system of injustice. Then God says these freed people will become his people. How do I know this? Verse 12 says once these slaves have been brought out of Egypt they “will serve God on this mountain.” The mountain is Sinai, the place where God gave the ten commandments (which begin with “I the Lord am your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery”). It was on Mount Sinai that Israel became God’s people.

This is key because central to what it means to be a part of God’s people is to be about God’s purposes. God’s people are those who join God in what he’s doing in the world. So the Exodus story isn’t just about people being liberated, it’s about people being liberated in order to liberate others. That’s the logic of God’s liberation.

The Jewish rabbi Louis Finkelstein once said that the Exodus event symbolizes “for all time the essential meaning of freedom – namely, freedom directed to a purpose. When Israel came forth from bondage, it was not simply to enjoy liberty, but to make of liberty an instrument of service.” Throughout the Old Testament God repeatedly tells Israel they’ve been liberated in order to liberate others. This gets at the idea of Tikkun Olam, repair of the world, an idea very much alive in Israel still to this day.

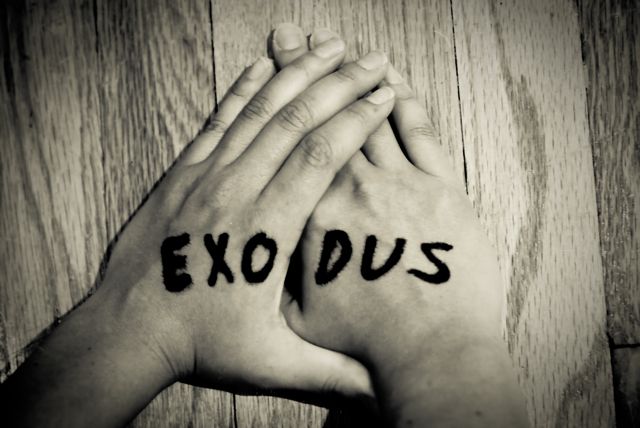

Liberation as jewelry (and tattoo)

In Exodus 13:9 God instructs Israelites to wear the Exodus story on their forehead and hand. Many believe this is the earliest mention in the Bible of tefillin, the Jewish custom of literally wearing scriptures in a small leather box on the head and hand during morning prayers. This is not terribly unlike some tattoos my friends have. Little do they know their ink is continuing an ancient practice!

However, rabbi Rashbam, the grandson of Rashi, offered a slightly different reading of this passage in the twelfth century. Rashbam said that since this command occurs within the context of a relational covenant, it should be read in light of an almost identical passage in Song of Songs (an entire book about relational covenant), where the beloved says to the lover, “Let me be a seal upon your heart, like the seal upon your hand” (Song 8:6). Following Rashbam’s interpretation then, Exodus 13:9 is a command to cherish the story of liberation as a precious amulet on the forehead and a costly bracelet on the arm – and again, perhaps we could add “as permanent ink on the skin” since people usually get tattoos to mark a monumental event or experience in their life. It’s essential, according to Exodus 13:9, that those who’ve been redeemed not forget the Exodus experience. This story not only reminds God’s people what they’ve been called to, it communicates something radical about God’s nature.

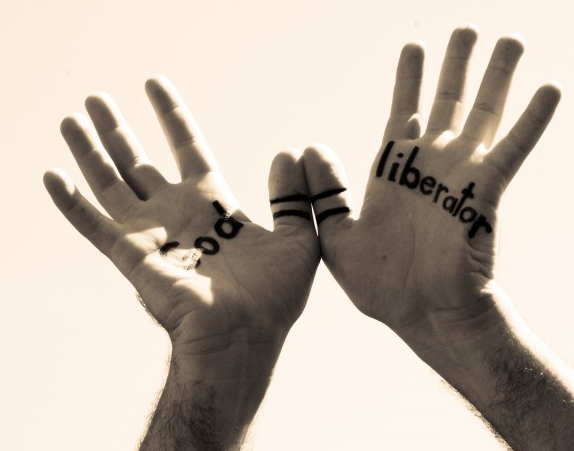

God = Liberator

Back to Exodus 3. Notice what happens after God announces he is going to bring these people out of Egypt. Moses asks God what he should tell the people if they ask who has sent him. God answers:

“I am who I am,” which can also be translated “I will be who I am,” and then in the very next verse God says, “This is my name forever, and the way I will be remembered from generation to generation.”

For centuries scholars have wrestled over the meaning of “I am who I am.” Some conclude that we’ll never know; the divine name is too mysterious. While I do believe that God will always be mysterious – he’s just too much for us to ever fully wrap our minds around – I don’t think that is what’s being communicating here. God isn’t evading Moses’ question. And God isn’t giving him a word puzzle to keep him stumped for years to come.

This passage wasn’t written in a vacuum nor should it be read in one. We must read it in its context, and when we do the fog begins to clear. God is communicating something deeply powerful about who he is. He comes to a group of poor slaves, tells them he hears their cries, sees their misery, and is going to rescue them from their oppressors. Thus when God tells Moses, “I am who I am,” he’s saying, “I am liberator. This is who I am.” Then God adds in the next verse, “This is my name forever, and the way I will be remembered from generation to generation.”

This text is more profound than we’ve realized in the past. Jews think Exodus is the first book, and at the beginning of the first book, the first time that God speaks he says, “This is who I am. I am liberator. That’s forever to be my name, and I will show myself as liberator to every generation from now on.”

Just marinate on that last part for a moment – God makes a promise that he will show himself as liberator to every generation. In fact, let’s stop here for the time being. We need to sit with and soak in this, and as we do, we can begin to ask questions which will be addressed in the next post: What happens when Israel forgets her God is liberator? What happens when God’s people forget that they’ve been liberated in order to liberate others? And the even the deeper question: has God kept his promise to show himself as liberator to every generation?